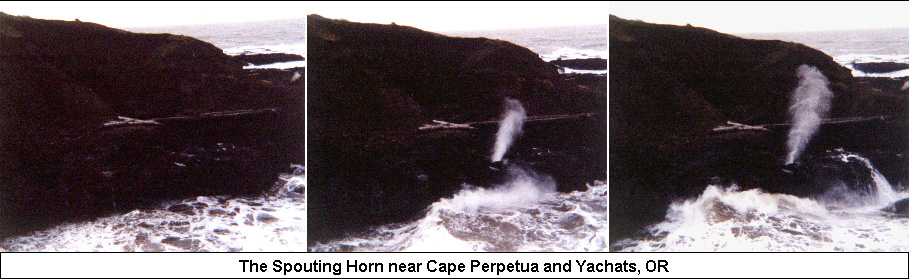

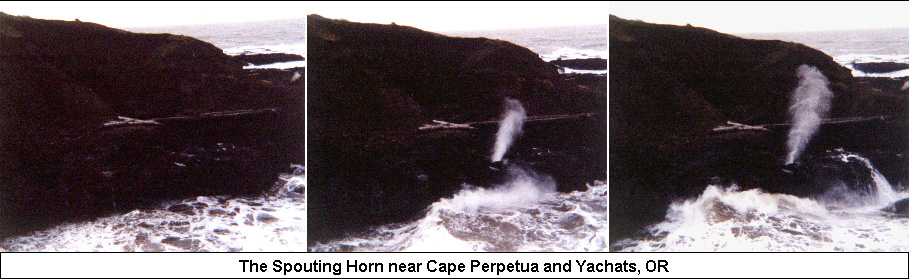

I sit overlooking Cook's Chasm, opposite the Spouting Horn. This is an overlooked spot on the Oregon Coast, unnoticed by those who are intent on driving. The wayside is poorly signed, inviting accidental discovery. And I have discovered this spot by accident today, even though this is not my first time here.

I am alone in one of Oregon's finest spots. The Spouting Horn is

our Old Faithful; rather than spewing hot water every hour, it spews cold

ocean brine every few seconds (but only when the tide is up). Every spout

is different, a tribute to the ocean's chaos. Sometimes the largest waves

do not cause the biggest spouts, as they crest over the horn and rush to

the back of the chasm. Sometimes the spout comes out at an angle, and sometimes

is blown above the level of the highway bridge to leave streamers and curls

of water hanging in the air even as the next eruption begins.

The Spouting Horn is by no means the only attraction. The water in the chasm is solid, marshmallow froth. Out in the ocean, the waves beyond the surf are painted pink by the Sun's first rays under a remarkably clear sky. Up the coast is Cape Perpetua. At the top of that crag, someone in red clothing stares over the vista for a few moments, perhaps spying me out on the rocks. Then the figure fades into the woods, and my eyes tell me that I am alone again. At my feet are tidepools, which I may visit at tomorrow night's low tide. Now they are a bath house for sandpipers, as a lone gull keeps watch. All the while the tide is coming in, and the ocean occasionally sets free a wave large enough to back me off my rocky perch just as it scatters the sandpipers and their shrill cries.

It is mid-November, yet salal bushes are still in bloom. Almost winter, yet I need only a sweatshirt. It is the Oregon Coast. It is home for a while.

11/19/95; 5:48 p.m.

It is dark, and I write this by flashlight as I look at the ocean from the dunes just north of Threemile Lake.

Threemile is large and pristine for a dune lake, with primary access by a three mile trail from the North. The trail is short for its length, winding through a spruce/hemlock forest full of small streams, log bridges, and mushrooms. The mushrooms surely captured the bulk of my attention today. At first I saw only a few waterlogged chanterelles, but deeper probes into the forest revealed fresh ones, a foray for tomorrow. Also around were the fly agarics with which I always associate this place, as well as Amanita pachycolea, Dentinum repandum, Boletus mirabilis, and hordes of Cortinarii and Russulas. I left all of these, but did pick a couple of Catathelasma imperialis. Tricholoma zelleri was common, but T. magnivelare, the sought-after matsutake, was nowhere to be found.

I continued toward the lake in order to reach it before nightfall. As I neared the campsite, I heard someone rustling the pines and feared that I would have to find another sleeping place. Instead, it was just a day-hiker with a bag of mushrooms. "Chanterelles and lamb's feet (Dentinum repandum)," he said. He had looked for matsutake, but hadn't found any. As I looked for a place to lay my sleeping bag, I saw a white mushroom cap protruding from the sand. I knew it was a matsutake, even before I smelled it. I put it in a bag, and set the bag down right next to another matsutake. A button of Leccinum manzanitae was nearby as well. Three older matsutakes appeared within a few yards, but I let them be due to their poor condition. I collected another nice one by flashlight before heading to the lake.

Threemile sits in a deep bowl that is not only a good spot for a lake but a superior echo chamber as well. I amused myself for a good, long time as I fired handclaps off the other shore. On my way back to camp, I watched a pair of planets fall into the sea. Venus and Jupiter, only a degree apart, took turns winking at me as they passed through a layer of clouds out in the ocean. Somewhere above Venus hovered faint Mars, unseen because of the clouds and the brightness of the twilight.

The planets are gone now, except Saturn in the South. Other stars peer through the coastal haze, and a breeze stirs the beachgrass as the breakers keep rolling in the now-invisible sea.

11/20/95; 2:15 p.m.

Waxmyrtle Beach Trail takes one along the shores of the Siltcoos River, which sports a salt marsh and a sandy beach in the lower reaches of its estuary. I park at the trailhead and break out a plastic collecting container. Evergreen huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum) is loaded with fruit along the trail. I sample from each bush, as the flavor of the blue-black BB's varies. The ones with a blue bloom seem particularly good; I pick a cup or two. The most common mushrooms along this trail are Russula rosacea, with bright red caps and flushed stems. They are inedible, but every mushroom hunter should chew on a small piece of the cap to see why. There is no flavor, only intense heat that threatens to blister the tongue. Other mushrooms are more mundane, and many are in less-than-prime condition. Case in point: two old matsutakes. These choice edible mushrooms eluded the eyes of many hikers before the maggots finally got the best of them.

After picking some more huckleberries, I desire sport. I venture into the woods to try to find matsutakes. From my adventure at Threemile, I know that they like to grow in sandy soil under shore pines. There is no shortage of that habitat here, but I wander for a long time without finding any. What type of understory do they prefer? Most of the specimens from Threemile came from ground covered only with needles, but that probably reflects the difficulty of sighting any mushroom in dense brush. I comb the area on and off the trail, finding only one specimen which was unlucky enough to pop up in the very middle of the trail and be summarily trampled. Tricholoma zelleri, the inedible relative, is everywhere, but there are no matsutakes. At last, I find two old and uprooted specimens, long past the point of being edible. In the Cascades, I could root around and find more nearby. In the dunes, matsutakes seem to be more solitary, but this is a good starting point. Only 25 feet away lurks a perfect button, round and fat and untouched by maggots or slugs. My search has paid off.

11/20/95; 5:30 p.m.

No planets will be seen tonight. Somewhere out in the ocean, a storm is approaching, promising rain for the last day of my adventure. I will probably camp in my car tonight, rather than on the shores of Siltcoos Lake as I had planned. Now, I stand at the tidepools at Cape Perpetua. The Spouting Horn is silent now; the tide is out. I navigate by flashlight and explore the hidden world of the rocky shore. In the pools are hundreds of small crustaceans, mainly shrimp. From time to time, a small fish darts in and out of my light. The contrast between wet sand and submerged sand is minimal, and one foot is wet before I drag myself back to my car.

Instead of a night hike to Siltcoos Lake, I will make do with a drive to Cummins Creek Trailhead. I would rather not take my chances with the coastal weather.

11/21/95; 11:23 a.m.

I am back where I was at the start of this journal. The tide is up, and the Spouting Horn is spouting again. The waves gain urgency from the storm which has not yet brought rain and is still out at sea. This morning I hiked from Cummins Creek across Gwynn Creek on the Oregon Coast Trail. I ventured up Gwynn Creek into the wilderness, and found more chanterelles and hedgehog mushrooms along with a dazzling variety of Amanitas. Resuming my course on the Coast Trail, I hiked another mile to Cook's Chasm.

A pair of small children run out on the rocks, tempting fate while their father trudges down to collect them. A few moments later, a sneaker wave drenches the spot where they had just been standing, and elicits a stern lecture from the father. The rest of the family is there as well. I can get no peace here, so I move up the shoreline. Narrow slots in the rocks, miniature chasms, channel the energy of the surf. It explodes with roaring froth at the end of the rocks, blowing great clouds of water aloft. I move with the wind so I can feel the moisture on my face. A different view can be had from Cape Cove, where both the Spouting Horn and these slots can be seen in the same frame. Perhaps most impressive is the view from the Coast Trail above and behind Cook's Chasm. The water in the main chasm is subjected to tremendous forces, so that it crashes with a fury all its own. The Spouting Horn is almost hidden by the highway bridge, but the hole at its source is more clearly seen from here than from below. Out there, the breakers are painted an early aquamarine as they curl under the Sun's radiance.

I pick one additional trail to hike before I return to Cummins Creek. The Giant Spruce Trail takes one up Cape Creek to a towering tree, 15 feet in diameter and 190 feet tall. (Another 35 feet was the victim of a windstorm and now lies across Cape Creek.) The base still clings to a nurse log which has long since rotted from existence. I crawl through this tunnel just for the heck of it. The Redwoods are in a class of their own, but our remaining old-growth Sitka Spruce stands are not bad at all.

11/21/95; 2:45 p.m.

The coastal weather can change quickly. As evidence, I am in a downpour as I gaze over foggy Siltcoos Lake. I had meant to stay here last night, hiking as I did to Threemile, but a forecast of possible showers changed that. The rain arrived this afternoon.

The wet weather is positive. Without it, there wouldn't be a coast. However, let me illuminate some of the negatives to be encountered here. Specifically, money and commercialization have dimmed my experience of the Oregon Coast. It used to be that one could pitch a tent at Honeyman State Park for $6 or $7. Now, it's twice as expensive and even day use costs money. Many National Forest campgrounds were free. Now, they charge $10 a night. Sure, the agencies need money, but this is ridiculous!

My sport of mushroom hunting has also been over-regulated. At the trailhead, I saw a "Forest Service Law Enforcement" vehicle, waiting to inspect anyone who enters or leaves the forest. Forest Service workers in cop vehicles. What's up with that, anyway?

The mighty matsutake, the mushroom which led to most of the regulations, is tasty but not worth $14 a pound. When it commands that kind of price from pickers, and is worth even more on the international market, the mushroom thieves go to work and pick what will give them a good price. Some regulation would appear to be necessary, but that doesn't make the scene any prettier. It is messier, as personal use pickers often face fees and restrictions which only commercial pickers deserve. Undoubtedly, the net snares recreational pickers while letting profit-mongering, greedy commercial pickers take all they want. I would not be disappointed in the least if the whole mushroom market evaporated and left recreational pickers at their leisure. That probably won't happen, though.

On the whole, commercial use of our remaining natural resources strikes a sour note with me. One can take either a South Route or a North Route to Siltcoos Lake. The South Route goes through a clearcut. When something like this, and the even more unsightly clearcuts on the South end of Threemile Lake, cannot be halted, it makes me wonder whether our whole environmental ethic has gone South.

It is still raining. A noise, seemingly from the treetops, startles

me. I realize it comes from the water, and see a group of over 300 coots

splashing their way up the arm of the lake. They apparently love the rain,

and either don't know or don't care about my existence. There is still

a lot of wildness left in the world, and I realize that I will have to

enjoy it while I can.